Award winning journalist Robyn Wilson shares her thoughts...

October 2021 marks the significant expansion of London’s Ultra-Low Emissions Zone (ULEZ) in the UK – the first since its introduction in 2019. From 25 October, ULEZ boundaries will grow to incorporate an area 18 times its current size, stretching from London’s north and south circular roads and covering many of the capital’s suburban outer boroughs. The expansion is the latest in a string of moves by political leaders across the UK and the rest of Europe to discourage the use of personal cars within their cities as they move away from a 20th century, petrol-based economy. From successful car-free systems implemented in Belgium and Birmingham or a public campaign calling for a ban on private cars in Germany, to the growth of the disruptive ‘trip economy’ mobility model – it’s clear cities are rapidly changing. So as city planners embark on these large-scale, dynamic social experiments to drive us towards a carbon-free future without personal cars, what are some of the considerations that cities will need to bear in mind and what benefits are they already bringing to their citizens?

Net-zero transport

Around one in five of London’s cars may be affected by ULEZ’s tougher standards, requiring them to be replaced or be hit with a £12.50 daily charge.

While that is punitive for those with older cars in particular, the benefits cannot be overstated. The Greater London Authority said the initial introduction of ULEZ in the capital saw the number of vehicles meeting emission standards double between 2017 and 2020, with a 44% reduction in roadside nitrogen dioxide.

“Pollution isn’t just a central London problem,” London mayor, Sadiq Khan, explained. “Expanding the ULEZ[…] will benefit Londoners across the whole of the city and is a crucial step in London’s green recovery[…]. We know pollution hits the poorest Londoners the hardest.”

Yet, there can be no argument that cars still play a central role in city transportation. While the last two years have skewed the figures, pre-pandemic (2017), 37% of journeys in London were made by private cars (including taxis).

"Pre-pandemic (2017), 37% of journeys in London were made by private cars (including taxis)"

And as anyone who lives in a major city will know, public transport networks can be overcrowded, particularly at peak times. With London’s population expected to grow from 8.7m to 10.5m over the next 25 years, it’s obvious that they alone will be unable to bear the burden of a net zero future.

With bans on petrol and diesel car sales coming in across Europe over the next 5-10 years, readying road networks for the mass switch to electric vehicles (EVs) will be a priority, particularly with EV sales having recently edged ahead of diesel. The implementation of a charging network, however, will need to rapidly pick up pace if it is to cope.

The Netherlands is leading the way in this respect with 66,665 charging points, far more than the next highest country, France, with 45,751 and Germany with 44,538, according to European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA) figures.

But with city populations expanding globally, are there other considerations to take into account, such as the rights of pedestrians? Could there be a new type of city design where walking and cycling are given priority over cars?

Car-free cities

In the last few years, the idea of car-free areas has been gaining traction. In 2017, Belgium’s city of Ghent introduced its ‘Circulatieplan’ to remove traffic from its historic centre. The idea was to reduce pollution and make it safer for pedestrians and cyclists, and to allow emergency services to get around more easily.

The city is now divided into six zones with differing rules such as one-way systems, no-go areas for cyclists, low-traffic and car-free areas. After some teething problems, where some businesses had to move, inner-city car trips have been reduced by 35%, the city centre is now flourishing and there is overwhelming support for the scheme.

So popular has it been that similar ideas are being closely looked at across Europe. Berlin Autofrei, a citizen’s group in Berlin, has been campaigning to get city’s leaders to make it illegal to drive private vehicles within the city’s 88 sq km ring (within the S-Bahn ring trainline) without a special permit.

"Inner-city car trips have been reduced by 35%, the city centre is now flourishing and there is overwhelming support for the scheme"

“[A car-free city] will bring a new level of freedom to the people,” says a Berlin Autofrei spokesman, discussing the benefits of the proposed ban. “For parents it will be the knowledge that their child can walk or cycle to school in safety, for commuters it will mean bus and tram services that are actually on time.

“Currently, if you want to hold a community street event or basically do anything that disturbs cars, you need a permit. That’s pretty crazy when you think about it as cars are not in use for 95% of the day. We want the reverse situation to become normal.”

"cars are not in use for 95% of the day"

In the UK, Birmingham Council has also recently announced that it will divide the city into seven zones, with restricted car use in the city centre, removal of parking spaces and cars diverted to the A4540 ring road to reduce inner-city traffic, in a plan that mirrors some aspects of the Ghent system.

But in major capitals the size of London, it is unlikely Ghent’s car-free model could be implemented fully, with many businesses depending on the road system. It begs the question: is there something that could bridge the divide between clean, green cities and the needs of business as well as individual convenience?

The trip economy

According to car service group, RAC, cars in the UK are only on the move for around 4% of the time, with 96% of their life spent parked up and unused – a stat that puts car ownership into perspective and makes emerging mobility models like the trip economy increasingly attractive for cities.

Proposed by Olaf Sakkers, partner at RedBlue Capital, the trip economy is an alternative proposal to the private car ownership model. The idea is to move away from purchasing vehicles towards purchasing trips, something that many people already do via car-sharing and taxis apps such as Uber and Lyft.

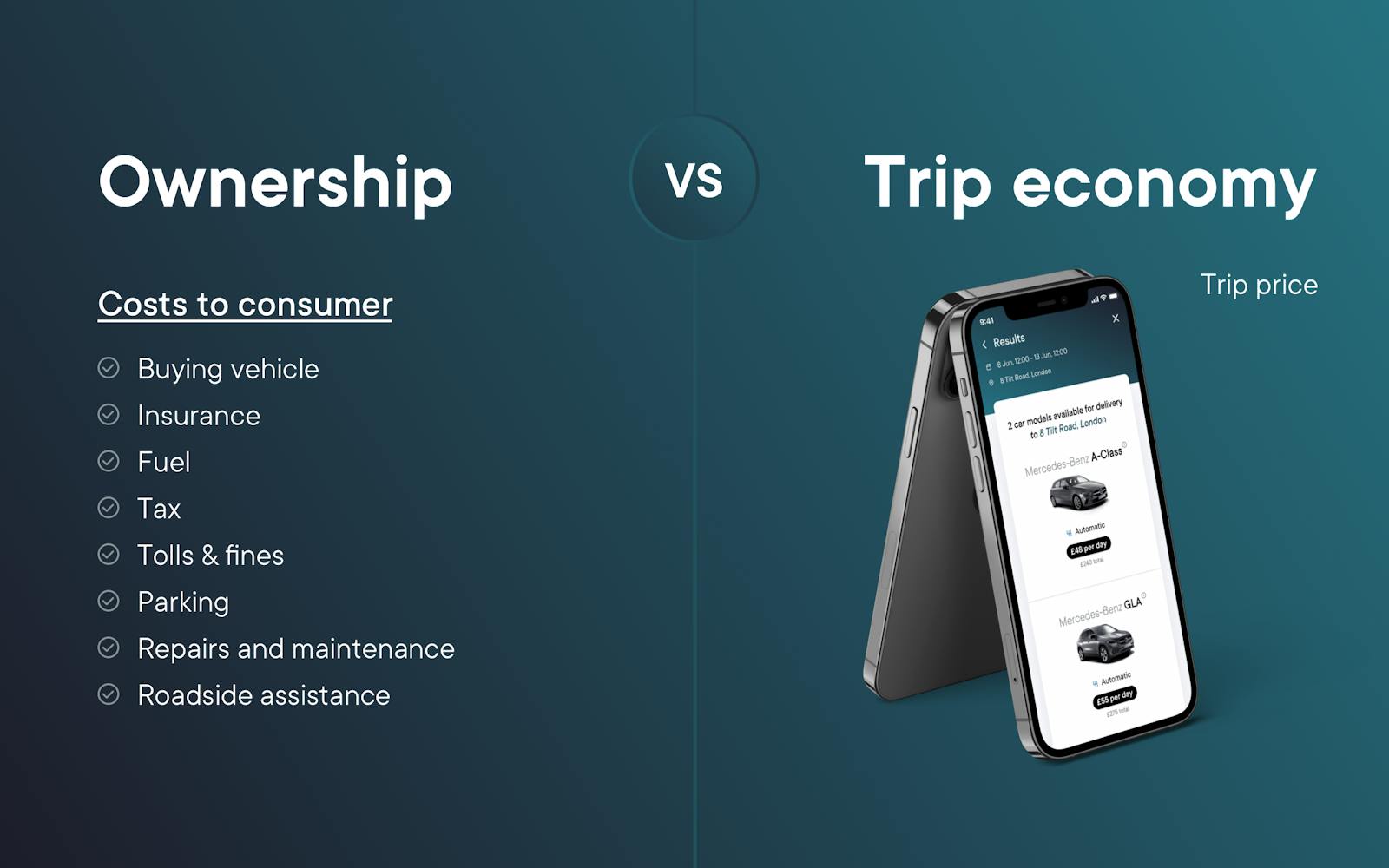

People have begun to realise it is more cost-effective to buy individual trips as and when they are needed rather than paying the upfront cost of a car (on average, €27,500 across Europe, according to Roadzen), as well as the running costs – tax, insurance, fuel, repairs and occasional fines (between €350-€700 per month in Europe, with western Europe at the high end).

"People have begun to realise it is more cost-effective to buy individual trips as and when they are needed rather than paying the upfront cost of a car"

It is for longer trips outside the city, however, that some people decide to keep hold of their cars – something which car rental company, Virtuo, is trying to address, says its CEO Karim Kaddoura.

“There are quite a few short-term micro-mobility and car-sharing options. But you can't truly move to a trip economy if you don't have the alternative for the occasional trip for long weekends, for European road trips, whatever it might be. So we are that missing piece of the puzzle to move to a full trip economy future.”

He adds, “Virtuo is already in London and Manchester, but we're also in France, Spain, Italy and soon to be launching elsewhere in the continent. We are in over 20 cities across Europe and operate around just over 4,000 cars across these cities. We can really provide a longer distance, convenient option for people.”

And if the trip economy can reduce the number of parked cars across Europe, it could also free up space for streets to have a more community focus, something that Sweden is trying with their one-minute city pilot, Street Moves.

The idea is to divert cars to alternative parking and ultimately discourage car ownership, instead installing modular street furniture like picnic tables, planters and social seating areas that can fit into the size of a parking space.

"if the trip economy can reduce the number of parked cars across Europe, it could also free up space for streets to have a more community focus"

By doing this, the Swedish initiative hopes to give the public more ownership over their streets and improve wellbeing by allowing residents to have a say in how these new communal spaces can be used, leading to better connections with their neighbours.

This is something that people want. A survey found that 75% of British people want to get to know their neighbours better, with only 5% saying they knew the names of people on their road.

The shift has already begun

Ultimately, moving away from car ownership may prove difficult, but the benefits of doing so could prove exponential. Many younger people in cities have already adopted a lifestyle where taxi and car-sharing apps are the norm, so it will come down to good city planning where priorities shift away from encouraging car ownership to a more flexible, dynamic model that will benefit everyone.

In numbers

- 1. Cars in the UK are only on the move for around 4% of the time (RAC)

- 2. Netherlands has highest number of EV charging points in Europe, totalling 66,665 (ACEA)

- 3. 96% of a UK car’s life is spent parked up and unused (RAC)

- 4. Personal cars cost on average between €350-€700 per month to run in Europe (Roadzen)

- 5. Virtuo operates 4,000 cars across Europe